AWK Program Structure

AWK scripts are organized into three main blocks:

BEGINblock- Body block (pattern-action block)

ENDblock

BEGIN { awk-commands }

/pattern/ { awk-commands }

END { awk-commands }

1. BEGIN Block

The BEGIN block is executed once and only once, before any input line is read. It’s typically used for initialization, such as:

- Setting output formatting

- Printing headers

- Initializing variables or arrays

- Changing field separators (

FSorOFS)

BEGIN {

FS = ","; # Set input field separator to comma

OFS = "\t"; # Set output field separator to tab

print "Name", "Score"; # Print table header

}

📌 Note: You can have only one BEGIN block in a script. If you have multiple BEGIN blocks in the same file, they will execute in order.

2. Body Block (Pattern–Action Block)

This is the core part of AWK. It’s executed once per input record (usually a line). The general form is:

pattern { action }

If the pattern is omitted, the action is performed on every line.

If the action is omitted, the default action is:

{ print $0 } # i.e., print the whole line

📌 You can have multiple pattern–action blocks in the same AWK program.

Examples:

# Print only lines that contain the word "error"$0 ~ /error/ { print }

# Print the second and third fields of every line

{ print $2,$3 }

# Print lines where the score (field 4) is greater than 60

$4 > 60 { print$1, $4, "PASS" }

3. END Block

The END block is executed once, after all lines have been processed. It’s commonly used for:

- Printing totals or summaries

- Final formatting

- Calculating averages

END {

print "Total records:", NR

print "Sum of scores:", total

}

🔁 It’s often used in combination with the Body block:

{ total +=$2 } # Add up scores from column 2

END { print "Total:", total }

Execution Order Summary

| Phase | What Happens |

|---|---|

BEGIN |

Run before reading any input line |

| Body Block(s) | Run for each line in the input |

END |

Run after all lines are processed |

Quick Analogy

If AWK were a cooking show:

BEGINis the preparation phase (set up tools, ingredients)- Body block is the cooking phase (process each item)

ENDis the plating/clean-up phase (summarize results)

Example

[jerry]$awk 'BEGIN { printf "Sr No\tName\tSub\tMarks\n" } { print }' marks.txt

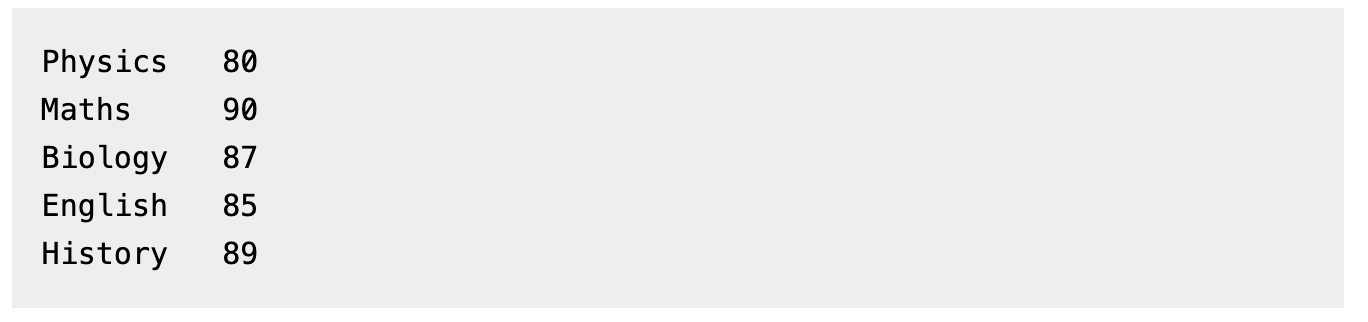

Let us create a file marks.txt which contains the serial number, name of the student, subject name, and number of marks obtained.

1) Amit Physics 80

2) Rahul Maths 90

3) Shyam Biology 87

4) Kedar English 85

5) Hari History 89

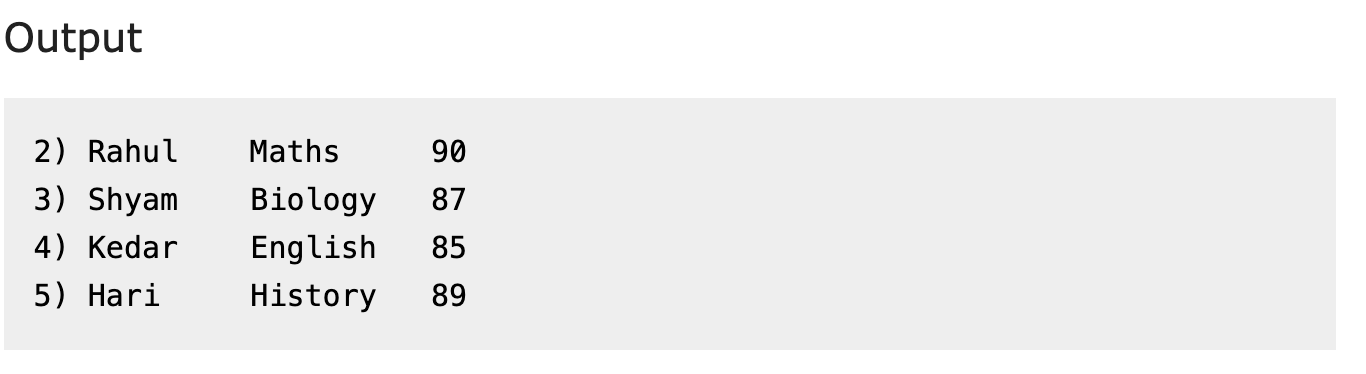

Output:

Sr No Name Sub Marks

1) Amit Physics 80

2) Rahul Maths 90

3) Shyam Biology 87

4) Kedar English 85

5) Hari History 89

AWK Command Line Syntax

awk [options] 'script' file ...

Printing Specific Columns

[jerry]$ awk '{ print $3 "\t"$4 }' marks.txt

Output:

(Check Image Path)

(Check Image Path)

Print all lines that match pattern "a":

[jerry]$awk '/a/ { print$0 }' marks.txt

(Check Image Path)

(Check Image Path)

Counting and Printing Matched Patterns

awk '/a/ { ++cnt } END { print "Count = ", cnt }' marks.txt

Printing Lines Longer Than 18 Characters

awk 'length($0) > 18' marks.txt

Variables in AWK

AWK is a full-fledged programming language, and like most languages, it supports variables. You can define your own variables or use AWK’s many built-in variables to work with records, fields, counters, environment data, and more.

AWK variables are untyped, meaning they can hold both strings and numbers, and they are created on the fly when first used.

Types of Variables in AWK

-

User-defined variables: You define and assign them as needed:

{ total +=$2; count++ } END { print "Average:", total / count }📝 Here,

$2refers to the second field in each line of input. In AWK,$nrefers to the nth field of the current line, and$0represents the entire line.

For example, if a line is:

Alice 85 Math

then:$1is"Alice"$2is"85"$3is"Math"$0is"Alice 85 Math"

-

Command-line variables: You can pass variables into AWK from the command line:

awk -v threshold=60 '$2 > threshold' scores.txt -

Built-in variables: AWK provides many useful built-in variables, such as:

NR: Number of records processed so farNF: Number of fields in the current recordFILENAME: Name of the current input fileARGC,ARGV[]: Command-line argument count and listENVIRON[]: Environment variables

Example: Print Command-Line Arguments

You can use ARGC (Argument Count) and ARGV[] (Argument Vector) to access the command-line arguments passed to the AWK program.

[jerry]$awk 'BEGIN {

for (i = 0; i < ARGC; ++i) {

printf "ARGV[%d] = %s\n", i, ARGV[i]

}

}' one two three four

Output:

ARGV[0] = awk

ARGV[1] = one

ARGV[2] = two

ARGV[3] = three

ARGV[4] = four

📌 Note: ARGC includes the AWK program itself as the first argument, and ARGV[0] is typically "awk" or the script name.

Print Environment Variable

[jerry]$ awk 'BEGIN { print ENVIRON["USER"] }'

Print Current Filename

awk 'END { print FILENAME }' marks.txt

Built-in Variables

FS — Field Separator

FS defines how AWK splits each input line into fields.

By default, the field separator is whitespace (spaces or tabs), but you can customize it.

Example: Split by comma (CSV)

echo -e "name,email\nAlice,[email protected]\nBob,[email protected]" | awk 'BEGIN { FS="," } { print $1, "=>",$2 }'

Output:

name => email

Alice => [email protected]

Bob => [email protected]

This sets the field separator to a comma and prints the first and second fields from each line.

NF — Number of Fields

NF is the number of fields in the current line.

Example: Print only lines with more than 2 fields

echo -e "One Two\nOne Two Three\nOne Two Three Four" | awk 'NF > 2'

Output:

One Two Three

One Two Three Four

These lines have more than two fields, so they are printed.

Example: Print the last field of each line

echo -e "apple banana\ncat dog elephant\nx y z" | awk '{ print $NF }'

Output:

banana

elephant

z

$NFgives you the last field of each line.

NR — Number of Records

NR holds the total number of input lines read so far, across all files.

Example: Print only the first two lines

echo -e "One Two\nOne Two Three\nOne Two Three Four" | awk 'NR < 3'

Output:

One Two

One Two Three

Example: Print line number + content

awk '{ print NR, $0 }' file.txt

file.txt

Hello

World

This is awk

Output:

1 Hello

2 World

3 This is awk

Example: Print lines 2 to 4

awk 'NR >= 2 && NR <= 4' file.txt

FNR — File-specific Record Number

FNR is like NR, but it resets to 1 for each new file.

Example: Track file boundaries when processing multiple files

awk '{ print "NR=" NR, "FNR=" FNR,$0 }' file1.txt file2.txt

file1.txt

File1-Line1

File1-Line2

file2.txt

File2-Line1

File2-Line2

File2-Line3

Output:

NR=1 FNR=1 File1-Line1

NR=2 FNR=2 File1-Line2

NR=3 FNR=1 File2-Line1

NR=4 FNR=2 File2-Line2

NR=5 FNR=3 File2-Line3

NRis the total line number across all files.FNRresets to 1 when a new file begins.

AWK Built-in Variable Quick Reference

| Variable | Description | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

$0 |

The entire current line | print$0 |

$n |

The nth field of the current line (e.g., $1, $2, etc.) |

print$2 |

NF |

Number of fields in the current line | print NF |

NR |

Number of records (lines) processed so far (across all files) | print NR, $0 |

FNR |

Record number in the current file (resets with each file) | print FNR,$0 |

FS |

Input field separator (default: whitespace) | BEGIN { FS = "," } |

OFS |

Output field separator (default: space) | BEGIN { OFS = "\t" } |

RS |

Input record separator (default: newline) | BEGIN { RS = "" } |

ORS |

Output record separator (default: newline) | BEGIN { ORS = "\n\n" } |

FILENAME |

Name of the current input file being processed | END { print FILENAME } |

ARGC |

Number of command-line arguments | print ARGC |

ARGV[i] |

Access individual command-line arguments | print ARGV[1] |

ENVIRON[x] |

Access environment variables (e.g., ENVIRON["USER"]) |

print ENVIRON["HOME"] |

IGNORECASE |

If set to non-zero, makes string comparisons case-insensitive | BEGIN { IGNORECASE = 1 } |

CONVFMT |

Format for number-to-string conversions (default: "%.6g") |

BEGIN { CONVFMT = "%.2f" } |

SUBSEP |

Separator for multi-dimensional array indices (default: ASCII 28) | Used internally with arrays |

Tips:

- You can redefine

FS,OFS,RS,ORSin aBEGINblock to change how lines and fields are split or joined. NR == FNRis a classic AWK idiom to detect when you’re processing the first file (in multi-file scripts).ENVIRONlets AWK scripts read environment settings likePATH,USER,HOME, etc.

Arrays in AWK

AWK provides support for associative arrays, which are key-value mappings. Unlike most programming languages, AWK arrays do not require declaration, and their keys can be strings, not just numbers.

Basic Usage: Creating and Accessing Arrays

awk 'BEGIN {

fruits["apple"] = "red"

fruits["banana"] = "yellow"

print fruits["banana"] # Output: yellow

}'

Deleting Elements from Arrays

Use the delete keyword to remove an entry from an array.

awk 'BEGIN {

fruits["mango"] = "yellow";

fruits["orange"] = "orange";

delete fruits["orange"]; # Remove the "orange" entry

print fruits["orange"] # Output: (empty)

}'

⚠️ Accessing a deleted element returns an empty string or zero depending on the context.

Simulating Multi-Dimensional Arrays

AWK officially supports only one-dimensional arrays, but you can simulate 2D (or even 3D) arrays by concatenating keys, usually with a comma or separator:

awk 'BEGIN {

matrix["0,0"] = 100

matrix["1,2"] = 200

print matrix["1,2"] # Output: 200

}'

You can use

SUBSEP(default is\034) as a consistent separator for multi-indexing.

Control Flow in AWK

AWK supports common control flow structures like if, else, while, and for. This allows for more dynamic logic inside pattern-action blocks.

Example: if-else Conditional

awk 'BEGIN {

a = 30;

if (a == 10)

print "a = 10";

else if (a == 20)

print "a = 20";

else if (a == 30)

print "a = 30";

}'

🧠 This works like any traditional programming language: the first matching condition is executed, others are skipped.

Common Use Case: Grade Evaluation

awk '{

if ($2 >= 90)

print$1, "Grade: A"

else if ($2 >= 80)

print$1, "Grade: B"

else

print $1, "Grade: C"

}' scores.txt

This script evaluates students’ scores in the second column and assigns letter grades.

AWK File Comparison Examples

Yes, awk can compare two files using its built-in features. Below are common use cases:

Example 1: Find Common Lines Between Two Files

awk 'NR==FNR {lines[$0]=1; next} $0 in lines' file1 file2

Explanation:

- Store lines from

file1in arraylines - For each line in

file2, check if it exists inlines

Example 2: Find Lines in file2 NOT in file1

awk 'NR==FNR {lines[$0]=1; next} !($0 in lines)' file1 file2

Example 3: Compare Based on First Field

awk 'NR==FNR {keys[$1]=1; next} $1 in keys' file1 file2

Example 4: Join Files on First Field

awk 'NR==FNR {data[$1]=$0; next}$1 in data {print data[$1],$0}' file1 file2

Example 5: Lines Only in file1

awk 'NR==FNR {lines[$0]=1; next} {lines[$0]=0} END {for (line in lines) if (lines[line]) print line}' file1 file2

Summary of Pattern-Action Structure

This structure:

NR==FNR {lines[$0]=1; next}$0 in lines

…is a classic AWK idiom. Here’s how it works:

NR==FNR {lines[$0]=1; next}

- Runs only on the first file

- Stores lines into array

lines nextskips to the next input line (avoids executing the second part on file1)

$0 in lines

- Runs on second file only

- Checks whether current line exists in

linesarray

If No Action Block?

If no action is given (like { print }), AWK defaults to printing the matching line.